A towering back-sail can change everything we think we know about prehistoric life. Researchers have confirmed a dinosaur species unlike its neighbors, and the detail that sets it apart rises along its spine like a banner in the wind. The find reshapes a familiar family of herbivores and opens a clear path for fresh questions. The anatomy, the behavior, and the environment now align in new ways, so the story grows richer. Everybody can expect clear facts, careful context, and lively science.

A towering sail that changes what we thought we knew

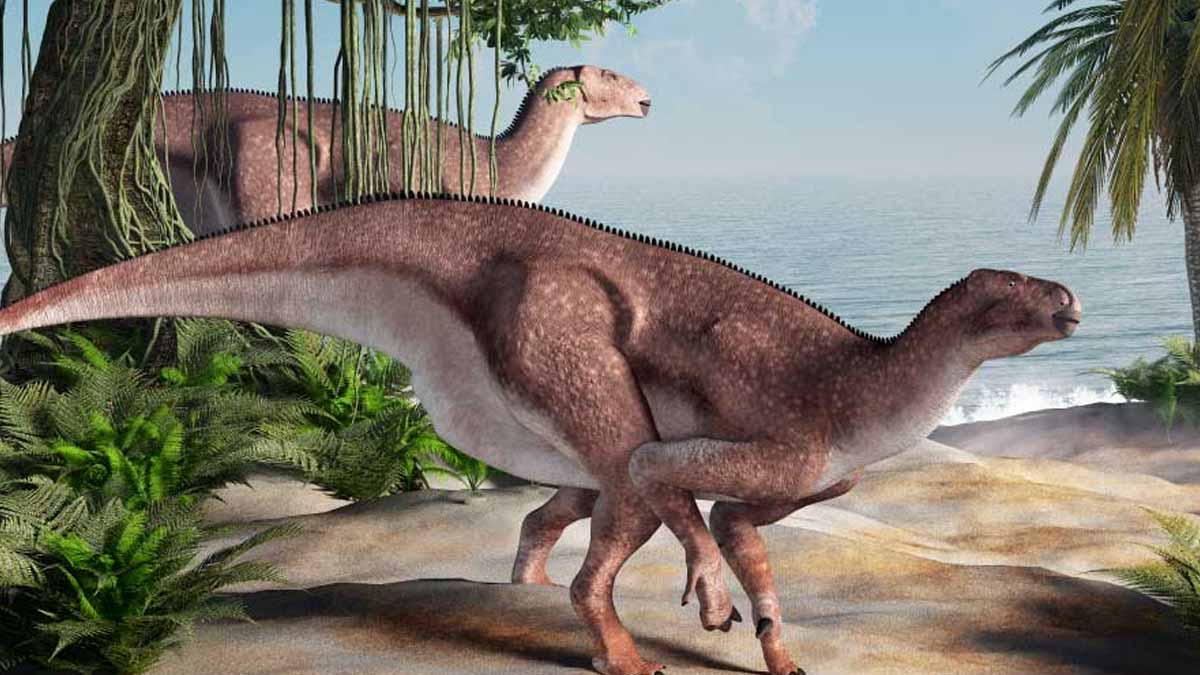

Paleontologists announced the discovery on Friday, highlighting a long, sail-like structure that runs down the animal’s back. The specimen, Istiorachis macarthurae, honors record-breaking British sailor Ellen MacArthur, and the name fits the striking profile. Bones surfaced on the Isle of Wight, off England’s south coast, in rocks laid down more than 120 million years ago.

The animal browsed among Iguanodon relatives, herbivores that spanned the Late Jurassic and Early Cretaceous. The Natural History Museum in London shared the news and stressed its scientific reach. The sail is not a small flourish; it defines the skeleton.

The vertebrae carry unusually long neural spines, and those spines drive the new identity. This backbone, when viewed in sequence, rises and falls like a wave and sets the animal apart.

How this dinosaur species emerged from a misread fossil trail

The bones turned up about 40 years ago and sat with a familiar label, assigned to one of two known iguanodontians from the island. That label made sense at the time, because the fragments fit broad patterns.

Retired doctor Jeremy Lockwood revisited the fossils during his PhD work and noticed a mismatch. The neural spines were far longer than expected, and the curve along the back did not match local species. He followed that clue, re-measured each element, and assembled a tighter diagnosis. The result elevated the fossils to a fresh taxon, and the paper went online Thursday in Papers in Palaeontology.

Lockwood also emphasized Early Cretaceous diversity on the Isle of Wight, and he expects more finds. The skeleton’s proportions back him up, because distinct anatomy often signals a different branch.

Signals, muscles, and what the sail likely did

Scientists tested ideas for the sail’s job because bold anatomy asks for function. One option, heat control, falls short in this case, since a thin sail packed with blood vessels would be easy to injure and could bleed heavily if attacked.

Another option, sexual signaling, fits the facts better, so the sail could work like a peacock’s tail and help mates find each other. The vertebrae also suggest muscles that required robust attachment points, so the elevated processes probably reinforced the trunk during locomotion and consumption.

Iguanodontians were shifting from smaller, mostly bipedal forms toward larger bodies that stood on four legs for longer periods. That shift demands solid support, and taller spines help. In that light, this dinosaur species blends practical strength with showy display in one elegant structure.

What this dinosaur species adds to the Early Cretaceous picture

Size matters for ecology, and the team estimates roughly two meters tall at the hips and near 1,000 kilograms in mass. Those figures translate to about 6.6 feet and around 2,205 pounds, which places the animal among hefty plant-eaters that could shape vegetation.

The Isle of Wight already held two iguanodontian species, so this newcomer raises the count and deepens local diversity. The timescale matters too, since the rocks span the Early Cretaceous, when lineages branched fast. Taller spines show up across related dinosaurs in that window, and the pattern points to both muscle support and visual signals.

Lockwood’s argument against thermoregulation, and for sexual selection, sits inside that broader trend. The island becomes a natural laboratory again, where form, function, and behavior meet in the fossil record.

From famous name to museum bench, a public science journey

The name nods to Ellen MacArthur, whose sailing feats match the animal’s “sail,” and that connection helps people remember the species. Public links matter because museum drawers hold many finds that only bloom when someone looks twice.

Here, a careful re-examination transformed a long-shelved specimen into a headline. The Natural History Museum underscored that re-use of collections as a driver of fresh knowledge. Field context still matters, and the Isle of Wight continues to deliver layers that record shifting climates and coastlines.

Each bone adds data points that guide reconstructions, while every mismatch invites tests. The likely arc is clear, and as Lockwood said, more discoveries will follow in the years ahead.

A closing note on what the spine suggests for behavior and evolution

Sexual selection likely drove the sail higher than utility alone, and that pressure can reshape bodies fast. The long neural spines still helped muscles, so the structure served strength while it signaled, which makes the design efficient. The animal stands roughly two meters tall and near 1,000 kilograms, and those numbers frame its life on land. The paper in Papers in Palaeontology fixes the name, and the Natural History Museum spreads the news. The Isle of Wight grows even richer in herbivores, and curiosity grows with it. A simple idea closes the loop: this dinosaur species turns a spine into a message, and the message endures.